Emergency Preparedness and Response: Extreme Heat

Policy Levers and Actions

There are several policy levers and programs that can and should be utilized to ensure that homes are able to protect residents against extreme heat temperatures. This page collects measures that can be implemented to improve thermal control in homes, raise the standards that guide housing to protect against extreme heat, and provide community services. These policies are especially important to provide support for low-income communities and families.

For responses to extreme heat events to be effective, coordination and planning at the state and local levels are important. The resources below offer resources to help mitigate heat impacts and reduce extreme heat events in the future.

Note that in discussions about the impact of climate change and the needed policies to counter it, there are (broadly) two approaches: mitigation and adaptation.

- Mitigation refers to efforts to reduce or slow the causes of climate change. Examples related to healthy housing include making homes more energy efficient, reducing the amount of energy needed to heat them.

- Adaptation refers to efforts to improve our ability to withstand current effects of climate change. Examples related to healthy housing include retrofits and strategies to reduce heat in the home during high heat events.

Because this guide is focused on the effects of extreme heat, most of the resources we have provided are more related to adaptation than mitigation; but both approaches are essential and related to healthy housing. These approaches can connect to each other, as well: For example, installing a cool roof can reduce heat in the home at the same time as it lowers energy costs and output.

The following subpages provide further information on specific policy levers:

- Fund Programs to Improve Homes and Support Residents

- Including Housing in Resilient Infrastructure Policy and Planning

Air Conditioning Availability: What Does the Data Say?

One piece of information that is important for gauging the impact of extreme heat on a community, and determining what kind of interventions and services are needed, is the number of residents that have air conditioning in their homes. Fortunately, national data provides some of this information: The U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) conducts a Residential Energy Consumption Survey (RECS). The survey includes questions about air conditioning. The last published survey, published in 2017, used 2015 data.

- In the Unted States, 87% of homes have some form of air conditioning. In total, 15.4 million homes lacked air conditioning in 2015; 2.8 million of those homes had an evaporative (“swamp”) cooler, which is an alternative to air conditioning used in dry climates.

- Buidings of two to four units are least likely to have air conditioning (80%).

- Among owner-occupied homes, 89% have air conditioning (81% central air) compared with 83% (62% central air) of rented homes.

- Of the homes with air conditioning, 74% had central air, 6% had three or more window units, 9% had two window units, and 11% had one window unit.

This data is also available by region:

- South: 95% of homes have some air conditioning.

- Midwest: 92% of homes have some air conditioning.

- Northeast: 85% of homes have some air conditioning.

- Mountain: 78% of homes have some air conditioning.

- West: 70% of homes have some air conditioning.

- In the Pacific Division, which includes the five states abutting the Pacific Ocean, 66% of homes have some air conditioning.

And by income level:

- Below $20,000: 80% of homes have some air conditioning.

- $20,000-$39,000: 84% of homes have some air conditioning.

- $40,000-$79,000: 89% of homes have some air conditioning.

- $80,000-$139,000: 90% of homes have some air conditioning.

- $140,000 or more: 93% of homes have some air conditioning.

The typical cost of a window air conditioning unit is $150-$500 to purchase, $50-$100 for installation, and $15-$40 per month for use. Read our technical assistance brief on the LIHEAP and WAP programs for information about programs that can distribute air conditioning units.

Providing Protection During Events

For more information on how to keep safe during a high heat event, see our Extreme Heat: Prepare and Act section.

Excessive Heat Events Guidebook

For public health and emergency managers.

According to the EPA, the negative impacts of excessive heat events (EHE) are largely preventable. This guidebook provides public health officials and community organizers with background on EHEs and also includes potential responses to extreme heat that can be implemented at the community level. [EPA]

Operating Cooling Centers During COVID-19

For public health, emergency managers, and anyone operating a cooling center.

The COVID-19 pandemic has complicated the accessibility of public services and spaces. This document created by the CDC sets guidelines for safely opening and operating cooling centers for federal, state, and local officials. It offers information on screening, physical distancing, air filtration, site cleaning, and personal protective equipment use. [CDC]

Include Thermal Measures in Codes and Standards

Using residential housing standards is an important lever to protect residents from high heat. Codes and standards should include thermal control measures, including requirements for how HVAC systems should be kept in good working condition and minimum and maximum temperature limits.

For more general information on how housing codes work at the local level, how you can find your local code, and how to leverage codes for healthy housing, see NCHH’s Housing Code Tools.

National Healthy Housing Standard

For property owners, elected officials, code agency staff.

NCHH developed the National Healthy Housing Standard to inform and deliver housing policy that reflects the latest understanding of the connections between housing conditions and health. The Standard is a living tool all who are concerned about housing as a platform for health. Individually and together, the Standard constitutes minimum performance standards for a safe and healthy home. It provides health-based measures to fill gaps where no property maintenance policy exists and also serves as a complement to the International Property Maintenance Code and other housing policies already in use by local and state governments and federal agencies. [url; NCHH]

Thermal control, ventilation, and energy efficiency are covered in Section 5 of the Standard. Some of the measures related to high heat include:

- 5.2.3. Heating Supply. If the dwelling unit is rented, leased, or let on terms either expressed or implied that heat will be supplied, heat shall be provided to maintain a minimum temperature of 68° F (20° C) in habitable rooms, bathrooms, and toilet rooms; and at no time during the heating season shall the system allow the temperature to exceed 78° F (25° C) in any room.

- 5.2.4. Forced-Air Systems. Any dwelling with a forced-air system shall have at least one thermostat within each dwelling unit capable of controlling the heating system, and cooling system if provided, to maintain temperature set point between 55° F (13° C) and 85° F (29° C) at different times of the day. The system shall have a clean air filter installed in accordance with manufacturer specifications at each change in tenancy and at least annually. This filter shall have a minimum efficiency reporting value of eight (MERV-8) unless the system is not equipped to use a MERV-8 filter.

- 5.2 Stretch Provision: The heating system shall be controlled by a programmable thermostat to avoid temperature extremes.

- 5.2 Stretch Provision: The dwelling shall have provisions to maintain the indoor temperature below a maximum of 85° F (29° C) through the use of mechanical air conditioning, ventilation systems, or passive design features.

- 5.3 Stretch Provision: HVAC equipment shall have the capacity to maintain indoor relative humidity (RH) at or below 60%.

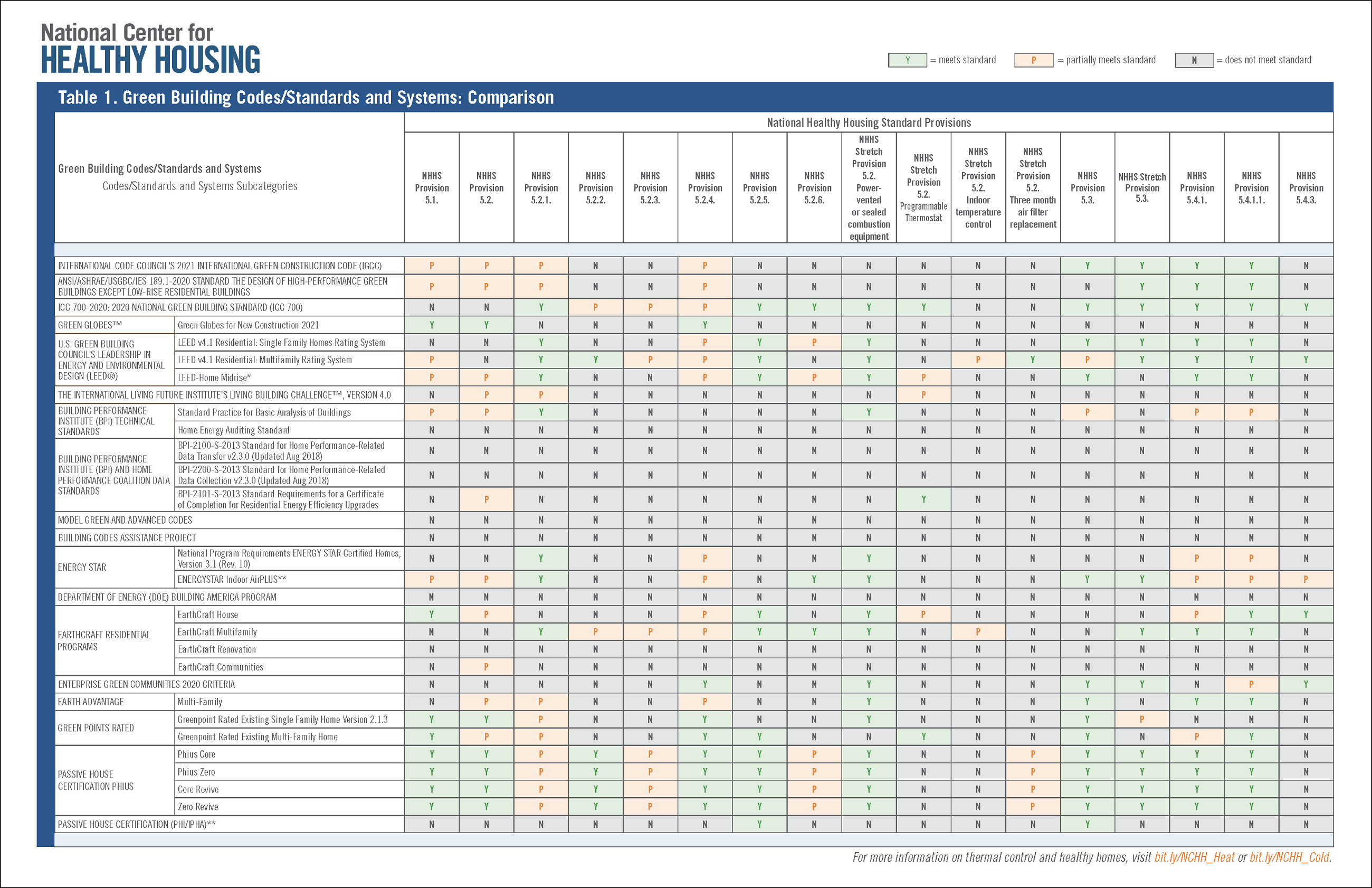

Green Building Codes/Standards and Systems: Comparison

For policymakers and developers.

For policymakers and developers.

This resource provides a quick comparison of thermal comfort measures of various green codes/standards, illustrating how green standards relate to each other and protect human health. NCHH compiled a list of 25 current energy efficiency, green, and weatherization codes/sub-codes, standards/sub-standards, and rating systems and compared each of their thermal comfort and core measures to those described in the National Healthy Housing Standard (using our Code Comparison Tool‘s Ventilation and Heating and Mechanical sections). The resulting resource shows (in table format) whether each code or standard meets the provisions described in the National Healthy Housing Standard provisions exist in each code/standard, citing the specific thermal comfort measure language of each. [pdf; NCHH, 2022]

Energy Efficiency and Weatherization Standards and Rating Systems

For building developers, code agency staff, energy agencies and programs, and homeowners.

This page collects several different programs and resources for energy efficiency and green standards in homes. [url; NCHH]

Infrastructure and Adaptations for Heat

The resources below are additional strategies for and examples of addressing urban heat island effects.

Adapting to Heat

For local and state public health, housing and community development, and emergency managers.

The Environmental Protection Agency’s guide to heat adaptations in urban settings provides local governments with planning resources to reduce heat vulnerability in both infrastructure and human health. The guide covers heat response planning, forecasting and monitoring, education and awareness, responses to heat, and infrastructure improvements. [url; EPA, 2021]

Heat Island Cooling Strategies

For community development, community-based organizations, and others working on community improvement.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency outlines strategies and technologies to reduce urban heat islands in this guide. These include increasing vegetation, installing green and cool roofs, implementing cool pavements, and practicing sustainable smart community growth. [url; EPA, 2021]

Green Roofs

For housing developers and agencies.

Explore the environmental and financial benefits of green roofs. This page, compiled by the U.S. General Services Administration, provides decision-makers with green roof benefits, cost-benefit analyses, and best practices. [url; GSA, 2021]

Cool Roof Calculator

For housing developers, agencies, planners, and homeowners.

Reflective cool roofs can significantly lower a roof’s surface temperature and reduce the energy needs of the building. This calculator, developed by the Oak Ridge National Laboratory, can be used by individuals and planners to estimate the annual savings that installing a cool roof will provide. [url; ORNL]

Urban and Community Forestry Program

For community development, community-based organizations, and others working on community improvement.

The U.S. Forest Service provides a variety of grants, resources, and tools to promote the development of urban and community forests. [url; U.S. Forest Service]

Case Study: Chicago, IL, Adapts to Improve Extreme Heat Preparedness

For public health, community development, planners, and emergency managers.

This resource from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency documents Chicago’s efforts to improve extreme heat preparedness after the 1995 heat wave. The page includes examples of adaptive actions as well as other EPA and CDC resources that state and local officials can use. [url; EPA, 2022]

[Esp] Adaptación al calor: Repercusiones nocivas para la salud

Para salud pública local y estatal, vivienda y desarrollo comunitario, y administradores de emergencias.

La guía de la Agencia de Protección Ambiental para adaptaciones al calor en entornos urbanos brinda a los gobiernos locales recursos de planificación para reducir la vulnerabilidad al calor tanto en la infraestructura como en la salud humana. La guía cubre la planificación, el pronóstico y el monitoreo de la respuesta al calor, la educación y la concientización, las respuestas al calor y las mejoras de infraestructura. [url; EPA, 2021]

[Esp] Estrategias de enfriamiento para las islas de calor

Para desarrollo comunitario, organizaciones comunitarias y otros que trabajan en la mejora de la comunidad.

La Agencia de Protección Ambiental de EE. UU. describe estrategias y tecnologías para reducir las islas de calor urbanas en esta guía. Estos incluyen el aumento de la vegetación, la instalación de techos verdes y frescos, la implementación de pavimentos frescos y la práctica del crecimiento comunitario inteligente y sostenible. [url; EPA, 2021]

Housing for Outdoor Workers

Outdoor workers are especially vulnerable to extreme heat. Our Adverse Health Effects and Susceptible Populations section has more information for this group about staying safe during high heat.

Farmworker Housing and Health in the United States: A General Introduction and Overview

For anyone seeking introduction this topic.

This report provides an introduction to the state of housing for agriculture workers in the U.S., including the types of housing that farmworkers frequently live in, housing conditions, and federal investments in housing. [url; Farmworker Justice]

Potential Resources for Seasonal Farmworker Housing

For advocates, housing providers, community-based organizations, and providers.

This resource from the USDA provides an overview of the various federal programs that have been or can be used to support housing for seasonal workers. [pdf; USDA, 2020]

Outdoor Workers: Policies

For local government, community-based organizations, and advocates.

This page from the California Healthy Places Index is connected to the Index’s indicator measuring the percentage of adults in the state who work outdoors. The page summarizes policy opportunities to address heat preparedness and response and create heat resilient workplaces, green and cool communities, and community power and connection. [url; HPI]

Latest page update: August 21, 2022.