Shoot for the Moon

by Christopher Bloom

There’s a rocket standing in for the Washington Monument this week.

It’s a projection of the Saturn V rocket that carried astronauts Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Michael Collins from the terra firma of the Kennedy Space Center upward through the stratosphere to rendezvous with destiny. The date was July 16, 1969. Four days later, 50 years ago today, with Collins orbiting above, Armstrong and Aldrin set the NASA lunar module on the site they named Tranquility Base. “The Eagle has landed.” They were the first humans on the Moon. At 10:59 p.m., Armstrong stepped into the soft, gray powder and made history again.

To gain proper perspective, it’s helpful to review a bit of history here: The first manned balloon flight took place in France back in 1783, and for 120 years, the hot air balloon and its cousin, the dirigible, were the only ways to fly, not that there weren’t hundreds of attempts – some modestly successful, some fatally flawed – to come up with a better way to get from here to there through the air. As we all know, everything changed in 1903 when Orville and Wilbur Wright revolutionized the airplane concept,* changing aviation history forever. Further advances over the next eight years yielded the first war planes; another eight years and Alcock and Brown would fly across the Atlantic Ocean. Not long after, the rest of us were flying, too, seated (un)comfortably aboard the first commercial passenger planes.

But before man had even conquered the sky, he was already aiming for the Moon. The first rockets were developed by Professor Robert Goddard in 1914; transformative advances occurred as early as the 1930s, spearheaded by Germany’s work with ballistic missiles. Looking forward to the International Geophysical Year of 1957-58, the United States announced in 1955 that it intended to launch the first artificial satellites into orbit; however, it was the Soviet Union that impressed the world on October 4, 1957, when their unmanned Sputnik 1 made the first of its 96-minute elliptical circuits around the Earth. (As for the U.S., its Vanguard TV3 satellite rose only four feet into the air before dropping back to the launch pad and exploding – on live television.) In the race to space, the U.S. was already far behind the Soviets. On May 5, 1961, Alan Shepard became the first American in space (beaten to it by the Soviet Union’s Yuri Gagarin); and on May 25, President John F. Kennedy addressed Congress, where he explicitly requested adequate funding to pursue the Moon. “These are extraordinary times. And we face an extraordinary challenge,” he began. Kennedy had seen from the Soviets that it was possible to fly through space; now he’d seen the Americans do it as well, and he was determined to push the United States to the next level, landing “a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth.” Game ON. At least that’s how it appeared.

The Eagle Is Grounded

You’re probably wondering what any of this has to do with healthy housing.

This weekend, our nation celebrates the 50th anniversary of the Eagle‘s landing on the moon. It’s been described as humankind’s greatest achievement, and one that is amplified by the fact that (if we consider our fateful 1955 announcement as the beginning) it took just six years for the U.S. to put a man in space, and another eight years to get him to the Moon and back. That’s not even 15 years from start to finish.

What we’re not celebrating this weekend – or any other – is the anniversary of our triumph over lead poisoning, because we haven’t conquered it yet. There are still 535,000 children under the age of six with blood lead levels above 5 micrograms per deciliter; that’s the level at which CDC recommends public health actions, though there are untold thousands more whose levels are below CDC’s reference level but are still suffering the permanent effects of lead exposure. Each year NCHH and the National Safe and Healthy Housing Coalition (and many other public health advocates) do our best to show Congress that lead hazard control is not only the right thing to do but also makes good fiscal sense, and they generally seem to agree, but the problem persists.

It’s not the money. Despite what the government would have you believe, the money is there. And we’ve researched lead poisoning thoroughly, so we have the data and the technology, and we know how to get to the finish line. So what’s missing? It’s the political will. The 1969 Moon landing has become John Kennedy’s legacy, but he was not initially in favor of the space program; in fact, he came around to the Moon challenge as a way for America to save face after the embarrassing Bay of Pigs fiasco. But the backstory, the intent, and the chain of events leading up to his May 1961 speech are not so important as the results here. What’s important is that Kennedy publicly declared his support for this specific goal, and Congress’ willingness to fund the initiative (estimated in 1961 to cost $22 billion by 1970) set the gears in motion. Ultimately, Kennedy sold himself on the idea, and then he sold it to America in Houston the following September, where, after having toured NASA’s Manned Spacecraft Center with astronauts and seeing NASA’s initial progress, he delivered a second legendary speech, which included this rationale: “Why choose this as our goal? And they may well ask, why climb the highest mountain? Why, 35 years ago, fly the Atlantic? [….] We choose to go to the Moon! We choose to go to the Moon…We choose to go to the Moon in this decade and do the other things not because they are easy, but because they are hard; because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one we intend to win, and the others, too.”

Had he not advocated for the mission, would the United States have flown to the the Moon? Maybe, but it’s extremely unlikely that NASA would’ve received the funding necessary to conquer Kennedy’s challenge by the end of the decade.

Flopnik?

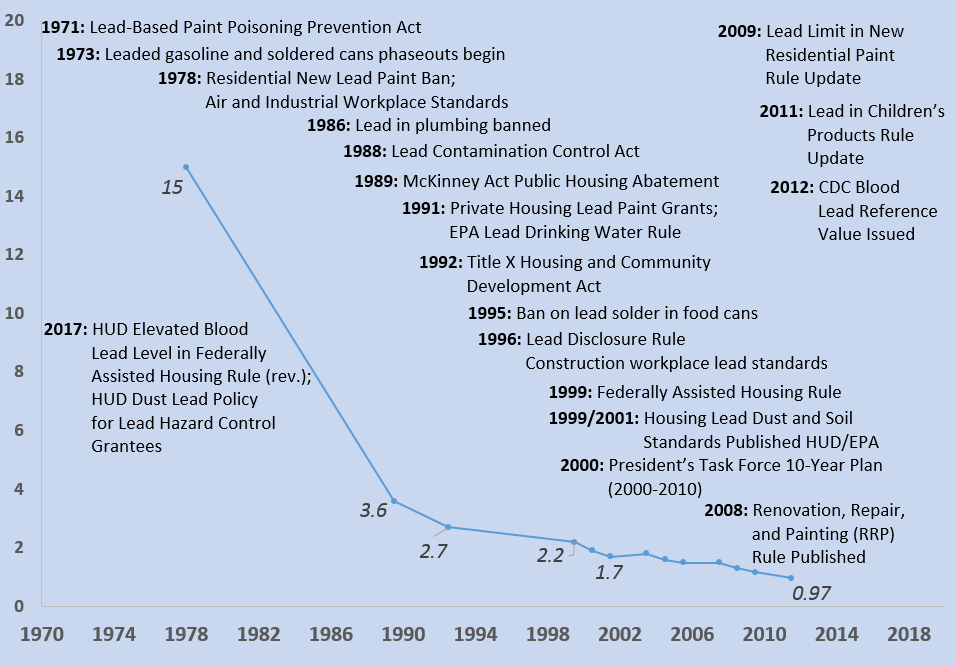

After nearly 50 years of legislation, the average level of blood lead has fallen from 20 micrograms per deciliter to just below 1 microgram per deciliter.

Meanwhile, back here on Planet Earth, we’re still fighting lead poisoning. As you may already be aware, lead poisoning can occur when humans are exposed to deteriorating paint in structures built prior to 1978, to soil that contains lead dust, to water that has passed through lead-lined service lines, as well as via hundreds of consumer products, many of which are still being manufactured today. The first major steps to reduce lead exposure came nearly 50 years ago, in the form of 1971’s Lead-Based Paint Poisoning Prevention Act. We’ve actually known for over two thousand years that lead is dangerous. When tetraethyl lead was added to gasoline in 1923, to reduce engine knocking, the decision was questioned and protested, but the lead stayed in. In 1978, the United States became one of the last countries to ban lead in paint for residential use; however, leaded paints are still available for specialized purposes. It was finally banned from our gasoline in 1996, and it’s still leeching into our water and found in our ammunition to this day.

Don’t get me wrong: Things have improved. The progress has been gradual but measurable. Congress does budget money every year for lead hazard control, and we are grateful for their commitment to fixing this problem. We know that many members of Congress would allocate more to the cause if the decision were theirs to make.

But let me ask you this: How many presidents since 1971 have told Congress that the lead problem must be solved by date certain? How many presidents have said to Congress: Lead poisoning is an extraordinary challenge, and we must work together to overcome it? I believe that answer is zero. When does lead poisoning and the exposure of more than 535,000 young children to toxic lead become an executive-level issue? When will a sitting president of either party admit to the nation that exposure to lead is still a huge problem, that the United States of America must do better, and here is our strategy to fix it once and for all? I’m not just talking about campaign promises, though discussing lead poisoning on the campaign trail is at least a start. I’m talking about action.

And what action or actions could a president support? Here are two that we can recommend:

- Find It, Fix It, Fund It is a lead action drive launched by the National Safe and Healthy Housing Coalition and NCHH in the wake of the Flint lead water crisis to find lead hazards, eliminate them, and build the political will to create key public investments and policies to do so. The initiative offers more than 50 recommendations for how to overcome lead poisoning by eliminating the many sources of lead exposure, modernizing regulations, and updating standards.

- 10 Policies to Prevent and Respond to Childhood Lead Exposure is a product of the Human Impact Project, a collaboration between The Pew Charitable Trusts and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The Human Impact Project assembled a team of researchers from such health and housing thought leaders as Altarum, the Brookings Institution, Child Trends, Trust for America’s Health, Urban Institute, and NCHH, among others.The 10 Policies report recommends a suite of actions for government at the local, state, and national levels to undertake that will not only help to end lead poisoning in the United States but also increase revenue and savings to the healthcare, education, and criminal justice systems.

But most importantly, whoever emerges victorious at the end of Election Night 2020 needs to speak up and give lead poisoning the prime-time attention it deserves. Lead poisoning was, is, and will persist as a national public health problem until the president, Congress, and the various state and local governments band together to enact a viable strategy to remove lead from homes, soil, water, and consumer products. To borrow from Kennedy once more, “I believe we possess all the resources and talents necessary. But the facts of the matter are that we have never made the national decisions or marshaled the national resources required for such leadership. We have never specified long-range goals on an urgent time schedule, or managed our resources and our time so as to insure their fulfillment.”

Let’s get to work.

*Officially, the Wrights weren’t the first to fly; however, they were the first to make a “sustained, controlled, powered, heavier-than-air manned flight.”

Christopher Bloom is NCHH’s communications and marketing officer. He joined NCHH in 2008 after nearly a decade in the real estate industry. In a previous role at NCHH, he coordinated a national Renovation, Repair, and Painting (RRP) training program, one of the most successful in the nation. He holds a Bachelor of Arts degree in English Textual Studies from Syracuse University.

Christopher Bloom is NCHH’s communications and marketing officer. He joined NCHH in 2008 after nearly a decade in the real estate industry. In a previous role at NCHH, he coordinated a national Renovation, Repair, and Painting (RRP) training program, one of the most successful in the nation. He holds a Bachelor of Arts degree in English Textual Studies from Syracuse University.